Boater’s Guide to Engines: The Internal Combustion Engine

January 16th, 2026 by team

PART I

by B.J. Porter (Contributing Editor)

Welcome to a new multi-part series we’ll be running over the next several months. The goal of this series is to get boaters more acquainted (or acquainted at all) with the engines we use for primary and auxiliary power.

There are a lot of engine topics out there, but we see the series shaping up into a few major parts. We will not get into extreme detail on the care and feeding of your engines yet, but we will eventually. The goal is to give people a stronger knowledge of how engines work, what the key differences are between the engine types, and what the relative strengths and weaknesses are between types of engines.

Over the next few months, we will cover:

- Internal Combustion Basics. How engines work to convert fuel to power.

- Diesel engines. More details on diesel engines, and how they differ from gasoline engines.

- Gasoline engines. More focus on gasoline engines, and their strengths and weaknesses.

- Electric motors. Hybrid and fully electric boats are becoming more popular, and electric propulsion has its own set of advantages and challenges.

Since we don’t like to drop a 5,000 word technical tome on you every month, we’ll split these major topics into more manageable segments. We will also spread them out over the year, so you won’t get an engine article every month.

And of course, if feedback and comments direct us to explore in a different direction or delve deeper, we will. So please bring on the questions!

Is it an engine or a motor?

The astute reader may have noted we referred to gasoline and diesel engines, but electric motors. Most people, even technical people, will throw the words engine and motor around interchangeably. And usually that’s harmless, but there is a very important distinction between the two. It’s crucial to use the right words in technical topics for clarity.

An engine is a mechanical device that converts power into motion using thermodynamic energy.

A motor converts electricity into mechanical motion.

Your car’s engine is a classic example of using a chemical reaction to create mechanical power by burning gasoline, which spins the engine and drives the wheels. On the same car, 12V power drives a motor that moves the windshield wipers back and forth. Many hybrid cars use a mix of a gasoline engine to provide driving power, combined with electric motors using stored power from a battery to assist or replace the engine.

It seems like a nitpick, but as we progress through the series, it will become clear why we use the distinct language.

What is internal combustion?

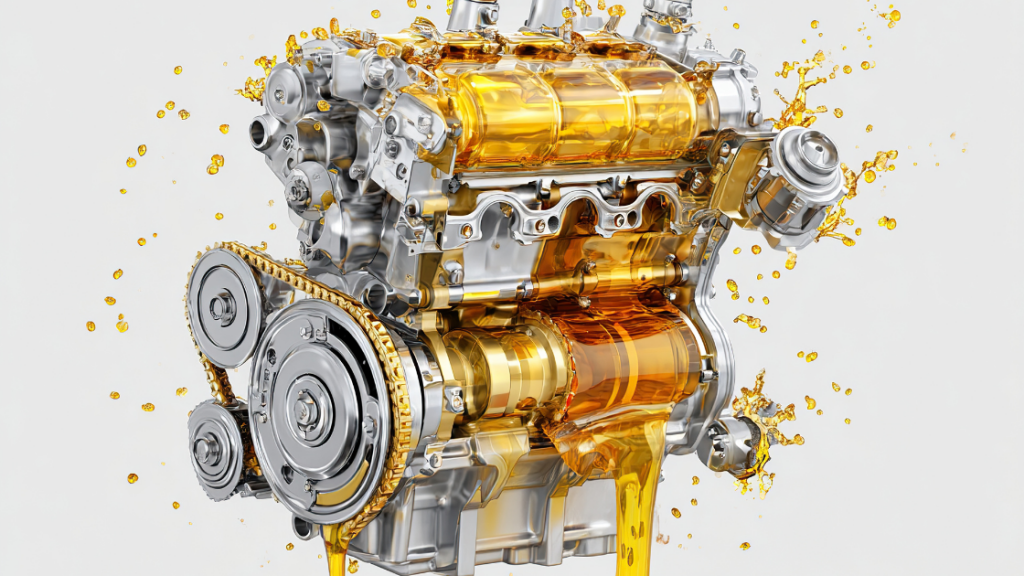

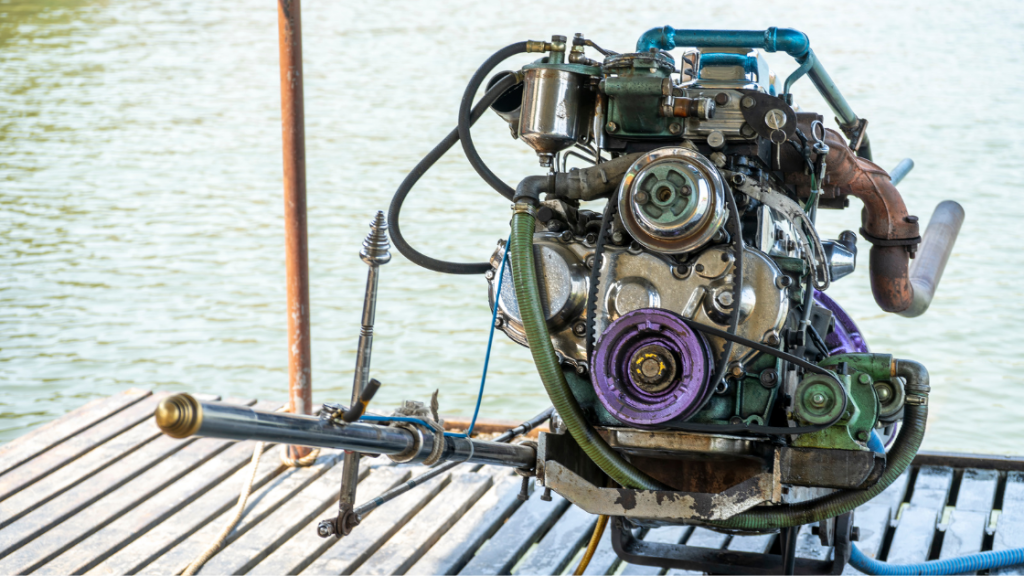

Modern boats use internal combustion engines. These engines burn fuel and convert it into power. Fuel and air enter the cylinder, get compressed, and the fuel burns, pushing down on a piston. This converts the chemical reaction (burning) into physical movement.

The vast majority of internal combustion engines are reciprocating engines with pistons that move up and down (or back and forth), with four distinct parts of the combustion cycle that create the power. Each of these four strokes is a distinctive step that has to be timed correctly for proper ignition and maximum power and efficiency. Some of you might ask about two-stroke engines, and how they’re different. Don’t worry, we’ll get to that.

Gasoline and diesel don’t burn on their own; they need oxygen for combustion. Getting the correct mix of atomized fuel and air in the cylinder at the right time is critical to proper combustion.

The Cycles/Strokes

Each step in the combustion process is the same for all engines, whether diesel or gasoline. Though the two types might handle some steps slightly differently. Four-stroke engines use valves to bring in air and sometimes fuel, and also to let exhaust gases escape. These valves open and close at precise times in the cycle. Two-stroke engines use different mechanisms for intake and exhaust.

These four strokes repeat continually, so the end of the last cycle (exhaust) leads right back to the next intake cycle.

Intake

During the intake cycle, the intake valves open so air and fuel can enter the cylinder. The suction of the piston pulling down may draw in the fuel, or a pump may inject it into the piston. That same suction can pull in air, but there are other ways to push air into the cylinder with fans or turbos.

Those details aren’t important to the underlying concept of how the engine works, so we’ll get to them later in the series as we explore topics in more depth.

Compression

Once the cylinder is full of a mixture of air and vaporized fuel, the intake valves close and the piston moves back up. This compresses the air/fuel mix. It raises the temperature of the mix and pressurizes the cylinder.

Ignition/Power

When the piston is at the top of the cylinder and the air/fuel mixture reaches maximum compression, ignition occurs. This may be from a spark in gasoline engines, or from the extreme heat generated in compressing the air/fuel mixture in diesels.

The burning fuel expands rapidly with substantial force, pushing the piston down. This motion turns the crankshaft.

Exhaust

Exhaust gases fill the cylinder after the fuel burn, and must be cleared before clean air and fuel can enter as the cycle repeats. The exhaust valve opens, and the piston pushes back up, forcing all the exhaust out of the cylinder and clearing it. The exhaust valve closes before the intake cycle, and it all repeats.

Two-stroke vs. Four-stroke

In the four strokes described above, the piston moves up and down twice for four distinct strokes, but there is only one power stroke. The other strokes clear the cylinder and draw in fuel.

The two-stroke engine must also complete the same four steps – take fuel and air in, compress the air/fuel mix, ignite it, and clear the exhaust. But it completes the process with two strokes, not four. So, every time the piston goes up and down, you need to pull in fuel, compress it, burn it, and clear the chamber.

Instead of using airtight valves to block air intake and exhaust output, the cylinder and piston combine several steps. So before the end of the power stroke, exhaust will start, and fuel and air are drawn into the engine before the piston reaches the bottom of the power stroke.

There are advantages and disadvantages of two-stroke and four-stroke engines, including trading simplicity and weight savings for less fuel efficiency and higher pollution. We’ll take a deeper dive into this in a later article.

We’ve described reciprocating engines with pistons moving up and down on a crankshaft. But there is another type of internal combustion engine called a rotary engine. These are also called Wankel engines after the inventor, Felix Wankel. They have tradeoffs to rotary engines and are superior in some ways, but also have limitations. They have had only limited application in marine engines. Since they’re not common, we won’t spend time on them unless we see a great clamor in the comments.

Turning fuel into power

So how do we harness pistons moving up and down to turn a propeller or spin up a generator to make power? We have to turn this reciprocating motion into rotary movement.

This is done with a crankshaft.

If you put the end of a piston on the center of a metal bar, you couldn’t move it up and down at all.

Now remember the last time you rode a carousel. Remember how the horses move up and down? Above the animals, a pole with bends in it rotates, and the poles holding the horses connect on the bent segments away from the center of rotation. As the main pole spins, the offset animal poles move up and down.

We use the same principle to convert the piston moving down from combustion into rotary motion. But instead of the rotating pole moving a horse up and down, a piston moving up and down rotates the crankshaft. A crankshaft has a series of offset attachment points for the pistons, with counterweights to keep movement even. It rotates around a centerline, but the pistons attach off center.

The piston is a round piece of metal with a flattened top. This has an articulated connection to a rod, and the rod has a round connector with bearings on the other end. This wraps around a crankshaft attachment point. When a piston pushes down during the power stroke, it makes the crankshaft rotate.

And that’s basically it – the up and down motion of the piston converts to rotating motion of the crankshaft. Whether there’s one cylinder or a dozen, they all connect to offsets on the crankshaft. The crankshaft spins, and that rotary motion can do anything from turning a propeller to spinning up an alternator, water pump, or generator.

At the front of your engine, you’ll see one or more flat disks at the center of the engine – these attach to the crankshaft. These connect to alternators and pumps with belts or gears, driving those devices when the engine rotates. At the other end of the engine, there’s usually a large flywheel, or weighted wheel, used to smooth out the power. And behind that is a transmission, a gearbox to adjust the engine rotating speed to the right speed to power your propeller via a propeller shaft or sail drive.

What’s Next?

This first entry in the series is a high-level view of the basics of how an internal combustion engine works. We’ve got a lot more to talk about on the topics of engines and power. Future topics will probably include:

- A closer look at the four-stroke engine, including the roles of the valves, camshafts, lubrication, and other four-stroke issues.

- A separate focus on diesel engines and gasoline engines, highlighting their differences and similarities.

- Turning power into propulsion, discussing transmissions and how your prop gets spinning the right speed and direction.

- Inboard versus outboard engines.

- Electricity with engines – how (and why) engines need power and how they make it, including basic DC alternators and larger AC generators.

- If there is interest, we can take a deeper look at two-stroke engines. Emissions rules in many countries (including the U.S.) have effectively stopped the sale of most new two-strokes, so this is a low priority topic. But it’s still interesting, as there are a lot of used two-strokes around, and you can still buy them in many countries.

- Electric and hybrid propulsion and powering. This is still an emerging technology. There are some interesting options hitting the market, but still some major limitations.

In these articles, we’ll get into maintenance and care tips, and how to get the most out of each type of power, and look at the best applications for each type.

And of course, if you have specific questions or would like a topic addressed, the comments are always open!

January 18, 2026 at 2:52 pm, David Higgins said:

Very nice