Sailing Skills: Why You Should Know How to “Heave To”

September 4th, 2025 by team

by B.J. Porter (Contributing Editor)

When people find out that I’ve done a lot of offshore cruising and crossed the Pacific, the conversation inevitably turns to weather. “Did you ever get caught in any big storms?” and “What’s the worst weather you’ve ever seen?” are common questions.

I’ve already talked to that last one in this blog, where I mentioned the worst conditions I sailed in were not out sailing in the world and crossing oceans, but coming back from a family trip to Block Island back when we lived on land. You never know when you might get caught out, or when you might need a break from sailing. Even on a weekend trip.

Power boaters, don’t click away without going to the end here; there’s a bit for you, too.

Heaving to is a skill all sailors – inshore and offshore – should have in their toolkit for safety and comfort. It sounds old-school, like some esoteric skill set from the age of clipper ships and square riggers, but it isn’t. It’s a powerful tool that can help you out no matter where you may sail.

What is “Heaving To?”

Well, it’s certainly not what you do after you’ve been a bit green around the gills and seasickness finally overwhelms you! But is can help with seasickness and discomfort by calming the boat’s motion.

Heaving-to is essentially “parking” your boat and slowing your rate of progress so your boat moves comfortably. This can settle your boat motion in bad weather and heavy seas, and give you a moment to pause for repairs, sleep, showers, or just to catch your breath and regroup.

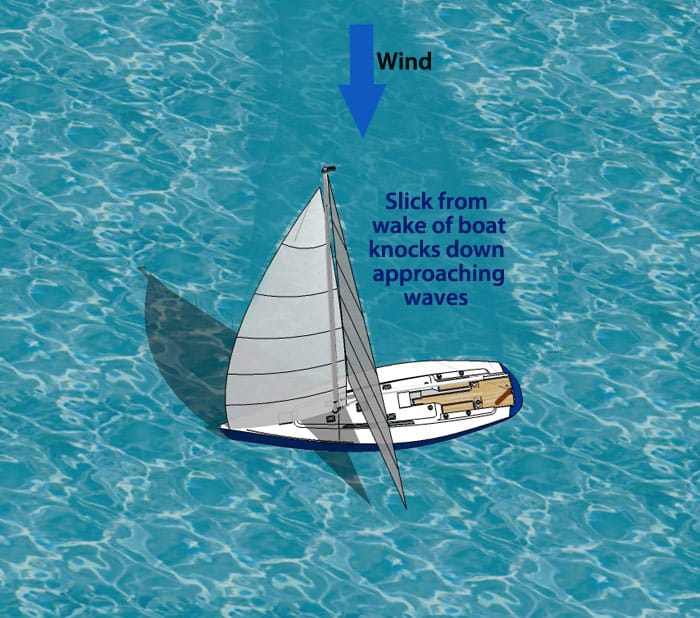

One pleasant effect of heaving to is that the off-the-wind drift of the boat leaves a smoothed out patch of water upwind, behind the drift. This slick can reduce or break up waves and chop, and that makes you a lot safer and more comfortable. Sailors in ages past would pour oil on the water in storms to get the same effect.

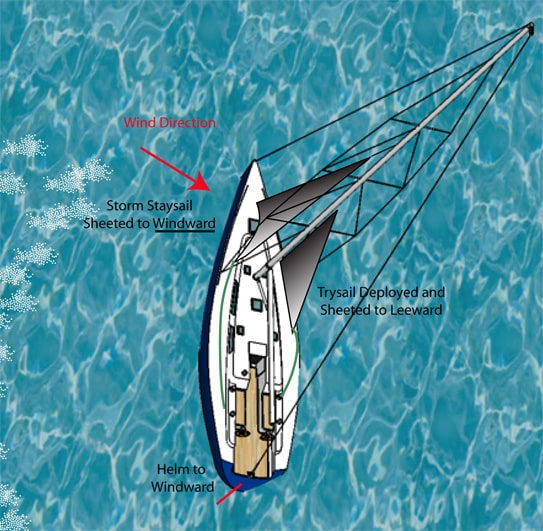

Coupled with some storm tactics and storm gear, heaving-to is an effective way to manage big storms and heavy weather, settling the boat down and easing motion.

When you heave-to, you stop your forward, directed sailing progress, back wind your jib, and turn your helm into the wind and lock it to balance the boat in a fixed, controlled drift downwind. With the judicious use of storm anchors, para-anchors or drogues, you can cut the drift on a hove-to boat to below a knot or two.

Heave-to How-to

The mechanism for heaving-to is the same, in theory, for all sailboats. Different boats heave-to differently though, and may require a unique balance of helm and sails to get “parked.” Boats with full keels will heave-to more easily than modern designs with fins or bulbs, and some more extreme keels may be difficult to stop with.

But the basic steps are:

1) Turn into and across the wind.

2) Back wind the jib, and lock it.

3) Turn the helm to windward.

4) Trim up the mainsail.

The backwinded jib pushes your bow away from the wind, and the rudder is turning you upwind as the boat slowly moves forward and the keel resists turning the boat. The trick is to get these forces balanced, so the boat moves slowly. You may need to make adjustments, especially if you have a very tall, high-aspect fin keel. If you have a narrow keel with a bulb like a race boat and a dagger-like rudder, you may struggle to hit this balance. In all cases, play with the rudder position and mainsail trim to see what works for your boat.

Once you’ve achieved a hove-to position, you’ll find the boat’s motion dramatically settled. Wave motion breaks up a bit, it mostly eliminates heel, and the boat will not roll violently.

When to Heave To

Through our years of cruising, we hove-to a few notable times.

- On our trip to the Caribbean, we arrived at the BVIs on a pitch-black, moonless night. We had concerns about negotiating the islands and harbors for the first time in the dark, as well as arriving in the middle of the night when customs and immigration might be closed. We hove to and left someone on watch until dawn.

- In the Tuamotus, where you have to time atoll passage entries exactly around tides or you can’t get in safely, we hove-to several times when we arrived early and needed to wait for daylight and favorable currents.

- En route from Tahiti to New Zealand, after a few days of sloppy beating to windward in a lot of chop, we hove-to for a few hours to rest, shower, cook a hot meal, and just catch our breath with a few hours of not heeling. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief as soon as the motion calmed, and a few hours later we were ready to slog onward.

Fortunately, we never needed to heave to in extreme weather.

From our list, it’s clear it’s a great way to stop your boat, whether you’re waiting for daylight or looking for a break from a long slog of a sail. Times you can heave-to include:

- Repairs, especially on the engine. Working in an engine room on a heeling, bouncing boat is no fun at all!

- Burning off some time, whether you’re waiting for daylight, tides, administrators, or the check-in time in a marina.

- Resting from sailing in hard conditions.

- Leveling the boat to cook a meal.

- Dealing with sickness, injury, or other on-board emergencies.

Heaving-to is easy, free, and takes little effort to do and undo once you learn how.

When NOT to Heave To

Heaving-to is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Sometimes, it’s a terrible idea.

Your boat is not stopped when you heave-to, you will move off the wind. So you need some sea room, and heaving to inshore for long can put you on a lee shore in no time. Any time you don’t have sea room downwind, you can’t heave to safely.

It’s critical to watch the wind when you heave to, especially within sight of land. If it clocks to a new direction, what was once open sea room may turn into a deadly lee shore.

Sometimes anchoring accomplishes the same goals and is often a better solution for a longer rest. If you can get to a protected spot with good holding in shallow enough water, it may be a better respite.

Consider your objectives, the conditions, and when inland, whether you can find a safe spot to anchor instead of risking a lee shore.

Practice Makes…

Yeah, you don’t need me to finish that statement. If you’ve been reading this blog for any time at all, you know when I talk about a new skill, I also fanatically exhort everyone to go practice it in easy conditions before you need it for real.

Heaving to is easy to practice; all you need is a day with a bit of wind. You can’t do it very well in light air, but 10-15 knots of breeze is a perfect low-risk practice opportunity. You just need a space with some sea room to leeward, and a bit of wind. When you get it down in lighter wind, try it again if you get caught out in some heavier stuff, too. Make notes on exactly how you need to set the sails and rudder, and also on how you move relative to the wind.

It is very important that you try it on your boat, because every boat heaves to a little differently.

Powerboat Heaving To

Though powerboats don’t have sails, they can still get caught out in bad weather when it’s safer to stop and ride it out instead of forging on through big wind and chop. And you can, with a big of cleverness, effect some like a to on a powerboat.

How, you might ask?

To heave to in a powerboat, slow the engine to just over steerage speed and keep the boat into or slightly off the wind with the autopilot or by hand steering. The boat slows and drifts more like a hove-to sailboat. A sea anchor or drogue will also help keep the bow into the wind.

While it’s not quite the same, it can give you some of the same benefits your sailing friends have, and is worth learning.

- Posted in Blog, Boat Care, Boating Tips, Cruising, Fishing, iNavX, iNavX: How To, Navigation, Sailing, Sailing Tips

- 1 Comment

- Tags: Heave to, storm, weather

September 12, 2025 at 8:46 am, fapello said:

This article is incredibly helpful! The clear explanation and real-world examples made heaving-to feel much less daunting. I especially appreciated the tips on adjusting for different boat types.fapello