Sailors Live By The Wind, But All Boaters Live With It

August 3rd, 2024 by team

by B.J. Porter (Contributing Editor)

To sail successfully, you need to observe with great care. You need to identify what the wind and the water are telling you and then find a way to execute, to reach whatever goal you’ve set, be that simply making it home or winning a race.

Sailors live by the wind, but all boaters live with it. The wind sets the tone for our day on the water – too much, and it’s too rough and dangerous. Too little, and it can be hot and still and sailors are in misery. And we can’t see it, we can only see the effects.

But what is it? Where does it come from? Why does it act the way it does, and how can we predict it and use it?

The answer is very complex, since there are several types of winds we see on the water every, and they combine in a complex blend which we can’t easily tell apart because it all looks like a single breeze. Forces act from global wind patterns from the earth’s heating, cooling and rotation, all the way down to local land effects. It makes prediction tricky, but the best sailors can absolutely can read it, use it, and know what it’s likely to do.

Global Forces

While wind and weather are a local effect, a lot of wind starts at the global level. While these effects cover hundreds or thousands of miles, they drive the motion of air masses and weather systems, and those cause wind effects. These forces explain the large scale, more reliable winds.

(All images in this section from Introduction to Oceanography Copyright © by Paul Webb, and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. )

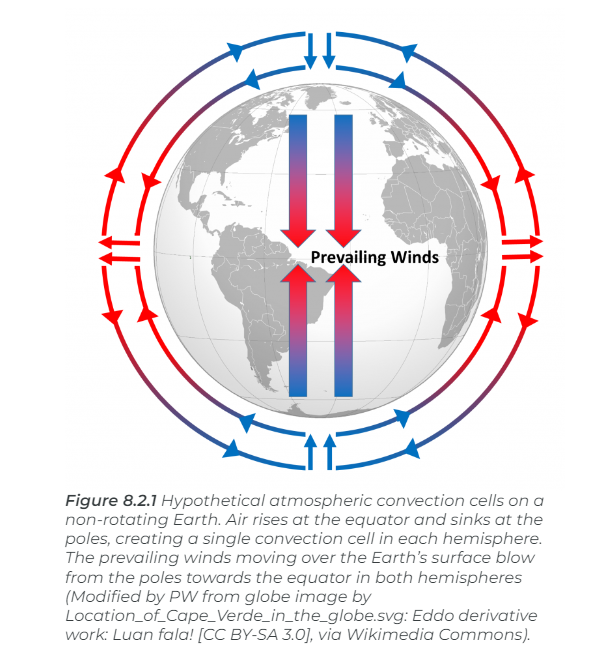

Heat and Flow

As air heats, it rises. This leaves space with less air and lower pressure, and low temperature air will flow into the void. Globally, this creates a general surface flow from the colder poles towards the equator, with the warmer air rising and flowing towards the poles at high altitude. As the air moves north, it cools and drops to the surface as part of the continuing cycle of flow.

If the earth didn’t spin, this would be the prevailing motion.

Coriolis Effect

But the earth is spinning. Picture a line of longitude from pole to pole on a spinning earth. The whole line rotates once per day, but each point on the line moves at a different speed. A point at the equator (0.0°) has to move the entire circumference of the earth in that day, or just under 25,000 miles moving at 1,042 miles per hour. But at the latitude of London, England (51.5072° N), the circumference of the earth is about 15,500 miles, and that point moves about 645 miles per hour.

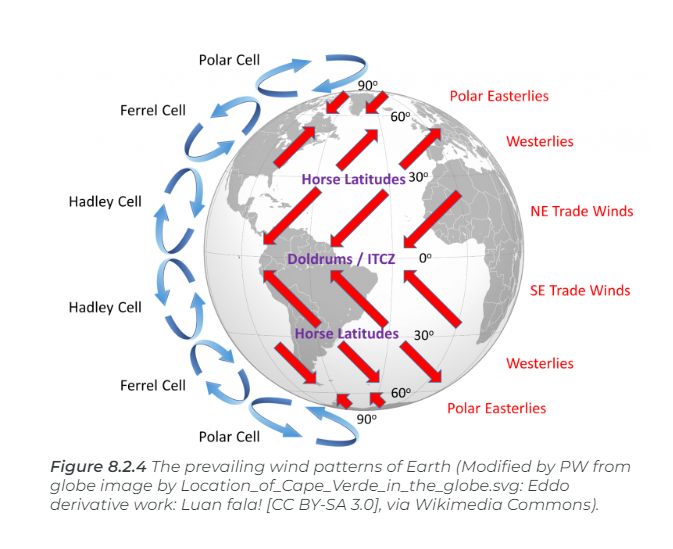

Why is this important? Air masses over the globe are dragged along with the earth’s motion, and different parts of a huge air mass are moved at different speeds. This has the net effect of deflecting motion to the right in the northern hemisphere, and to the left below the equator. It can also impart rotation onto an air mass, affecting wind.

While the total effects are too complicated to get into here, the Coriolis forces on air masses cause three major convection cells in each hemisphere, roughly every 30° of latitude. These cells cause the large prevailing trade winds, westerlies, polar easterlies, and light wind zones which dominate global weather patterns.

(Apologies for skipping the detailed explanation. You can read this chapter of Introduction to Oceanography for much more detail.)

Air Masses and Gradient Winds

All liquids flow from high pressure to low pressure. Adjacent air masses with different pressures and temperatures will have a flow from high pressure (cold) systems to low pressure (warmer) systems.

Because of the Coriolis effect and the motion of system, this flow is not directly towards the center of lower pressure. It tends to be more along the lines of pressure (the isobars, remember those from last month?), usually deflected on a tangent to the isobar.

As various pressure systems move through an area, the winds caused by their motion and pressure gradients cause the wide variations in wind and weather from the global prevailing conditions.

Many of these effects are also above surface level, and measured surface winds may be different from higher altitude winds.

Local Effects

The global effects set the prevailing wind conditions for a region, but local effects can have an enormous impact on the wind boaters see. The prevailing summer winds in New England are southwesterly, for example. But racers on Narragansett Bay will tell you about the local afternoon breezes that build on clear summer days, and on an even more local level, sailors know about land features which predictably cause variations in wind direction and strength.

On Shore / Sea Breeze

Water temperature is fairly constant, and it takes a lot of time and energy for the sea surface temperature to change more than a degree or two. But land heats and cools rapidly. Think of the temperature on a beach or parking lot throughout the course of a summer day – from cool in the morning to foot-scorching heat in the afternoon you wouldn’t want to walk on barefoot.

The rapid heating of land usually causes a local land effect wind called an onshore breeze or a sea breeze. During the day, the land surface heats while the surface of the water stays reasonably constant. Air heated by the land rises, and cool air from over the water rushes in to fill the void.

Note this effect is towards the shore, so it’s not directional with larger weather systems. It will combine with prevailing winds, but in the absence of a larger gradient wind, an on-shore breeze can sometimes be the dominant force on any afternoon. And sometimes the larger wind will cancel it out.

Land effects

Cliffs, hills, mountains, peninsulas, and other land structures can all affect wind flow. Wind flows over the land, but air flowing over land has different friction and drag than air flowing over water. Tall structures can force the wind around or over them, changing the flow boaters feel on the on the water. If you want to see this effect, light a candle, then blow it out. Next, light it again, but put your finger between your mouth and the flame and blow again. Notice a difference?

This is often notable in constricted areas, or closer to shore. A wind shadow of light or disturbed air can project quite far from shore, and racing sailors who know their local wind patterns have a distinct advantage. Sharp wind shifts, drops or increases and velocity, and other effects all tie directly to land features as the wind flows past them from certain directions.

It’s not a cause of wind so much as an effect on it, though on-shore breeze from a particular mass of land projecting into a body of water can generate wind effects.

Storm Cells

Large storm systems across hundreds of miles have fairly consistent winds. But storms aren’t uniform, and some regions have smaller storm cells with their own convective wind patterns, or multiple cells in a single region experiencing storms.

As a storm cell forms, it warms in the middle, and air rises. This draws air towards the cell from all directions, leading to winds which may shift and clock through the compass as the cell passes. If you end up inside the storm cell when it’s raining and fully formed the wind flow generally reverses and flows out of the storm again.

The motion of these smaller systems also deflects the wind direction.

What to Watch For

Outside the obvious bad weather like storms, boaters need to watch the wind to plan for more comfortable and safe trips.

Sailors will look to sail, of course, and the wind direction plays a big component in where they may choose to sail on a weekend. But other conditions will affect all boaters.

Wind vs. Current

When the wind and the current are in the same direction, there’s little to worry about. But wind against the current can lead to some unpleasant and even dangerous conditions.

Whether you’re sailing in southern New England and figuring out how to get around the north end of Martha’s Vineyard, or trying to cross the Gulf Stream, opposing wind and current directions can lead to large, steep chop and very rough conditions.

Any time you’re passing an area with a current stronger than a knot or two, check the wind direction. Even a short cut between islands with a current behind you and wind in your face can lead to large standing waves at the exit!

Anchoring Safety Comfort

A sharp swing in the wind when anchored can lead to anchor dragging, so for the safest anchoring, wind predictions are crucial. Check the prediction for any large swings or changes in velocity. Going to bed anchored in a light southerly sheltered by land is delightful. Waking up in the middle of the same night to twenty-knot northerlies blowing over five miles of open water and fetch is not.

Racing wind

Small shifts in wind direction and strength can make big changes on a short race course, so racing sailors need to look for patterns in the wind behaviors. Look for oscillations in direction and pulses in strength, and try to see how these may relate to the time of day, sea breezes, and land features.

Pulling it together

The sum total of winds you’ll see on the water is a very complex calculation of forces and direction vectors from the large weather patterns down to the local afternoon on shore breezes. It’s difficult for amateurs to figure it exactly. What you’re looking to do is figure what is likely, and be prepared for it.

Fortunately, weather forecasting has gotten pretty good at predicting local winds, even hourly for some locales. Free web sites can give broad predictions, but racing sailors and bluewater cruisers often subscribe to more detailed predictions.

Before you head out, check the wind predictions. Watch for local land effects where you sail, and if you’re headed some place new, check in with local sailors to learn about specific features which affect the wind you’ll see. And always watch for wind against current.

And remember, it’s still an estimate of a very complex system, and you may expect considerable variation from any prediction from local effects.

- Posted in Blog, Boat Care, Boating Tips, Cruising, Fishing, iNavX, iNavX: How To, Navigation, News, Reviews, Sailing, Sailing Tips

- No Comments

- Tags: coriolis, forecasts, fronts, heat and flow, Wind

Leave a Reply