Nautical Terminology 101 – Standing Rigging

September 8th, 2023 by team

by B.J. Porter (Contributing Editor)

Rigging comes in two forms – standing rigging, or that which is permanently fixed to the boat, and running rigging, which is the lines and other devices that can be easily removed and adjusted. Next month, we’ll talk about running rigging, because that has a whole mess of names too. This month, we’re discussing the fixed components of your rig: the mast, and the wires, rods, and connectors that support the mast and hold the heavy sail loads.

Rigging Concepts

At its simplest, a mast is a single pole sticking up in the air that holds a sail. Smaller boats may have unsupported rigs, as do some rig styles like cat or Freedom rigs. But most masts from the earliest days of sail use a series of wires and ropes to stiffen it, so the mast could carry more sail area without collapsing. The mast is stiffened with wires from the hull and deck to prevent it from bending or breaking.

Standing rigging in modern yachts is usually one of two types – wire rigging, or rod rigging. As the name implies, wire rigging is a large cable made from smaller wires twisted together into an immovable rope, and rod rigging is solid pieces of metal rod. Rod is stronger by weight, tougher, and stretches less. But it is more expensive than wire.

Newer high-end yachts may use composite rigging from materials like carbon fiber or high modulus lines. These advanced materials offer great weight savings, for very high strength and durability. But they are quite expensive and not common on production boats for large markets.

Stays

Stays are fore and aft wires (remember “fore” and “aft” from last month?) which connect at or near the top of the mast. They keep the rig stable in a fore-and-aft direction, so it doesn’t fall forward or backwards.

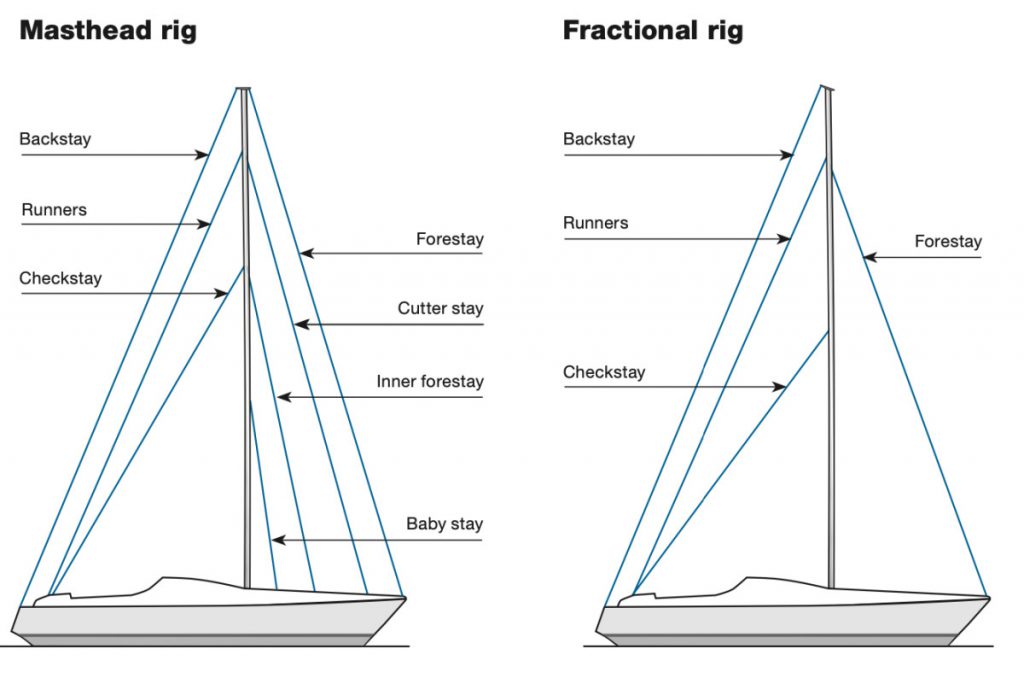

The aft stay is called the backstay, though split stays are possible. The forward stay may be called the headstay, if it attaches to the head of the mast. But it may also be called the forestay, especially when the stay attaches somewhere down from the top of the masthead. Many sailors use headstay and forestay interchangeably.

Some boats may also have a second or even third inner forestay. No sails fly from the backstay, but the forestay/headstay usually holds the headsail, either a jib or Genoa. Inner forestays carry staysails.

Some older rigs may have a baby stay for additional support. This wire runs from the lower mast to the deck, and does not fly a sail. This arrangement is uncommon on modern designs.

Some boats have running backstays, checkstays, or both. These are a hybrid of standing and running rigging, since they are easily adjustable without tools and can be removed. Though they’re often permanently attached to mast fittings and disconnected at deck level and stowed.

Both types of stays add stiffness to the mast or straighten it in some sailing conditions. Running backstays attach higher on the mast, and checkstays attach closer to the middle of the mast to stop the mast from pumping or bowing.

Shrouds

The shrouds give port/starboard stability to the rig, to keep it from flopping sideways. The horizontal bars coming out of the sides of the mast are the spreaders, which increase the angle of the shrouds from the mast. This change in angle allows for more load to hold the rig up.

Shrouds may be continuous or discontinuous. Continuous shrouds run one wire or rod from masthead to deck without a break. Discontinuous rigging breaks into segments between spreaders. This allows different sized rigging at different heights to save weight. We number discontinuous rigging segments starting at the deck with V1, V2, and so on, to describe them accurately.

The topmost shroud, known as the cap shroud or uppers, is the angled section that meets the top of the mast.

Diagonals

Inside the shrouds, most rigs have cables running diagonally in the upper mast sections. These diagonals run from the mast just below the spreaders to an attachment point near the base of the shrouds. On multi-spreader rigs diagonals will also run from the lower spreader ends up to the mast below the next set of spreaders.

We number diagonals D1, D2, etc. from the deck upwards. Note that the cap shroud may be numbered like or referred to as a diagonal.

Lowers

The lowers often refers to the lowest diagonal attached to the deck. Some boats may have multiple sets of lowers, with fore and aft wires.

Bedding and Attachment Points

Chainplates are attachment points for shrouds, though they are rarely visible on newer boats. Older boats would have an actual plate on the outside of the hull for the shrouds and standing rigging. Many new boats have internal chainplates. These are protected and are often behind panels if they aren’t visible against the hull down below. Because they are bedded into the hull, we may think of them as deck hardware. But solid, stout chainplates are an integral part of the mast support structure.

Advanced Topic: Rig Tune and Adjustment

Before a serious race, people adjust the turnbuckles and shrouds on the boats at the dock. They are “tuning” the rig for the day’s expected conditions, and may even send someone up the rig between races to make adjustments.

All the shrouds and diagonals can be tensioned to make different parts of the rig tighter or looser. Before heading out into light air, racers will often loosen up the rig to allow for more droop and sag to give more power in the light airs. Or they may tighten everything down in anticipation of a big breeze, where the sails are set more for speed since there is plenty of power with a lot of wind.

The first goal of tuning is a straight mast, the next is the amount of rake or pre-bend the mast will have when the rig is unloaded. Most boats allow for backstay tension adjustments while sailing, but setting up a good tune for the conditions can make or break a light air race.

For casual sailors and cruisers, the goal of rig tune is a straight rig that’s tensioned properly to handle a variety of conditions without re-tuning.

September 17, 2023 at 5:19 am, Dave Pritchard said:

How long before the two rigging types should be replaced? What are signs they need replacement?

September 19, 2023 at 2:00 pm, B.J. Porter said:

That depends on your boat use and your type of rigging.

The general guidelines are about every 10 years for wire, and 15 for rod. But your mileage may vary with…your mileage.

When we were out cruising our insurance company was quite particular about the age of our rigging, and we ended up replacing it in New Zealand. We put it off for several years by having professional rig inspection reports for the insurance company.

On the other hand, I never had an insurance company say a word about my rig age when I was coastal cruising and racing. Though they might eventually.

The most important thing you can do is drop your rig every couple of years and do a detailed inspection for wear, rust intrusion, etc. A professional rigger can do a good non-intrusive inspection, and if there are issues they can do more in depth testing.

If you’re not crossing oceans and putting 10,000+ miles of travel on your boat every year you may get longer from your wires!

September 21, 2023 at 10:29 pm, Duncan said:

Should cover synthetic (e.g. dyneema) a little more. It’s not just for high end expensive boats. In fact, it’s often cheaper than wire or rods, and is fairly common on smaller boats and trimarans.

September 24, 2023 at 8:10 pm, B.J. Porter said:

Good thoughts for another article on rig materials in a little more detail.