What Boaters Needs to Know About Tides & Currents

May 6th, 2025 by team

by B.J. Porter (Contributing Editor)

Years ago, when I was first learning to race sailboats, one of the top sailors in our fleet took a deep swing in towards shore during a race. I stayed out in the middle of the bay, because I liked the wind where I was and thought it would hold there well for us.

And we got crushed.

Why? Primarily because the guy who’d been racing in those waters since he was a kid knew exactly where to go to get relief from the current in the incoming tide. And we sat out there in deeper water, getting pushed backwards by a knot or two of current while he sailed in slightly worse air but against a fraction of the current.

Currents and tides can have a major impact on your navigation and boating experience, not just when you’re racing. And there are very few places in the world where you can completely ignore them. So it’s worth spending a little time demystifying currents and tides so you can get the best impact you your boating.

What is tide?

The moon causes most tides in our ocean.

Every object exerts a gravitational pull on every other object, no matter how large or small. Although the forces are too small to measure or even see accurately, gravity attracts even two marbles in a candy dish to each other. The larger an object, the greater its gravitational pull on objects around it.

So a very large object like the moon exerts enough pull on the earth to be felt. While the land doesn’t move, the ocean is both massive and fluid, and the vast waters of the ocean shift in response to the pull of the moon.

As the moon revolves around the earth, the direction and amount of pull changes, making the oceans effectively slosh back and forth in their basins. There’s a fairly complex bit of math calculating the exact amount of gravitational pull on the ocean’s waters, and it includes the position of the moon relative to the earth, the sun, and the oceans in question. But we know enough to predict accurately the timing and magnitude of every swing in the tidal cycle.

What about currents?

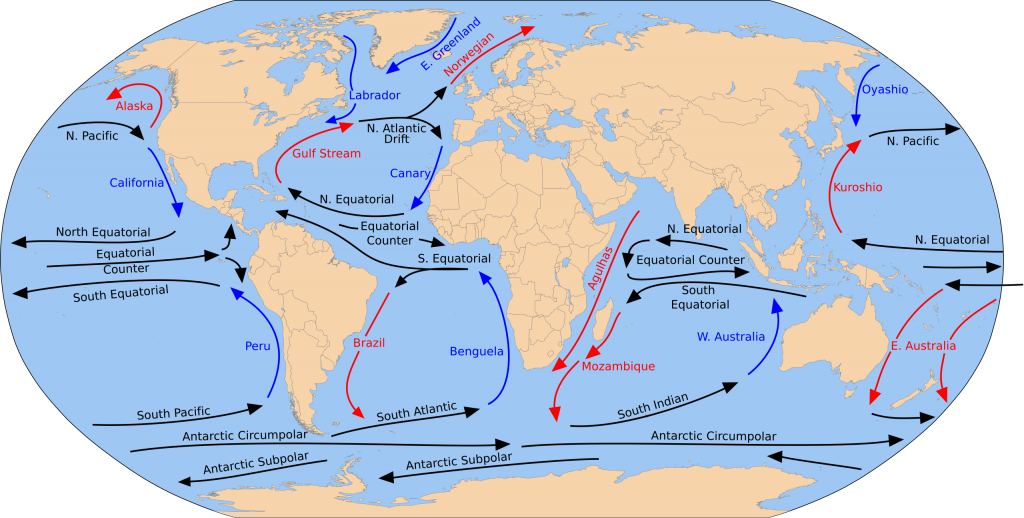

A current is just water moving in one direction. It may move from one place to another, such as when the tide comes in. Or it may be part of a larger rotational movement in the world’s oceans.

Tides into currents

Near shore, tidal swings mean a lot of water is moving into shore or away from shore. That water’s movement is current, and it’s affected by the geography of the areas the water is moving through.

In the example I gave at the beginning, there was a lot of water flowing into Narragansett Bay. The deepest part of the bay experiences the highest current velocities, where most of the water rushes in. However, the greater area on the shallower sides of the bay spreads the water, resulting in a noticeably lower current flow.

Anywhere you see a narrowing of water passages, deeper channels, or broad shallows, you will see changes in current velocity.

Ocean currents

Not all currents are tidal. There are several offshore currents with other causes, and these will affect you when you sail away from land.

Some, like the North Equatorial Current (NEC) are driven primarily by trade winds. This current spins into the Gulf Stream and meets other currents as the Atlantic Ocean circulates. All oceans have large rotating currents and countercurrents, and sometimes there’s little to do to avoid them.

But many times you can plan your travels to minimize the harmful current effects and maximize the benefits. Before racing to Bermuda, navigators use satellite images and expert predictions to determine the best place to enter the Gulf Stream. A good stream entry can get the boat moving with an eddy current increasing speed from behind, and a bad one can leave you wallowing into the teeth of the northbound current.

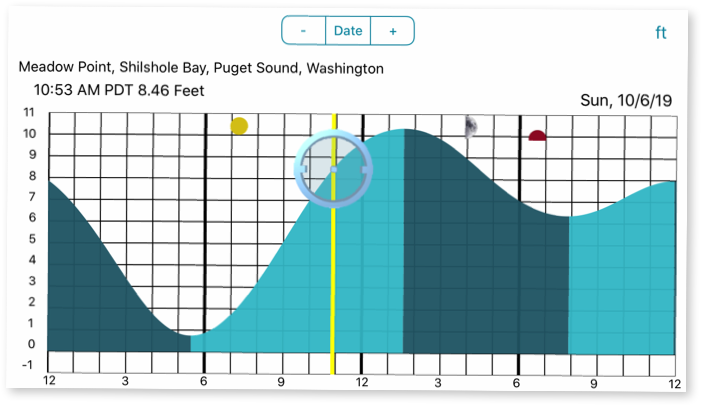

Tidal Cycles and Current Planning

A normal lunar tide cycle repeats twice for each revolution of the earth, with some time change because of the movement of the moon during the day. The tidal cycle advances approximately one hour each day in much of the world, especially the eastern U.S. So if it’s high tide at 7:00 a.m. today, the second high of the day will be around 7:30 p.m., and tomorrow the first high tide of the day will be around 8:00.

These are estimates, of course, as the specific timing of the tide varies with your location in the world. And there are some places where the moon isn’t much of a factor. Those places don’t have the same twice-daily tides North Americans are used to.

Fortunately, we accurately project these tides, and tide tables are readily available for places with primarily lunar tides.

However, while tide times are exact, the water movement does not stop and start instantly. For example, if a tide is high at 9:18 a.m., it’s true it should reach its highest point around 9:18 a.m. However, there’s a tremendous mass of water flowing inland as the tide comes in and that has a lot of momentum. So at 9:18 in the morning, there still may be water flowing with visible current as the tide moves to slack. But depending on the location, it may take an hour or more for it to go completely calm, then move in the opposite direction.

So tide tables are plenty accurate to plan your travels around, but you can’t expect the tide to stop and start precisely like a clock-work mechanism at the predicted times!

Navigating with Current

Anyone with extensive experience sailing around Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket is going to be familiar with the Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book. This small yellow paperback is a critical resource for navigating the tricky tides and currents in all the narrows and cuts around all the islands.

The only way you’ll get through Vineyard Sound without an Eldridge’s is luck, and bad luck can leave you sailing or motoring in steep chop as it piles up from winds against terrible adverse current.

But with your Eldridge in hand, you can own and optimize the currents. It allows you to figure out the approximate currents on any day or time in the year, from which you can plot out the best time to leave your home port to catch the best currents and miss the worse ones. Good planning can make a difference of many hours in arrival time and give you a more safe and comfortable trip.

To use a tool like this or any other, you need to know how to plot a course and plan a route. With this route, you’ll need to estimate your speed for the trip, and when it will put you at different places in different times. Many navigation tools are quite good at these estimates, if you set up your boat speed parameters correctly.

Using a tide and current book, your steps will be:

1) Plot your course from beginning to end, assuming no tides or currents.

2) Estimate your speed and determine your position at set intervals along the course.

3) Look up the time you plan to leave in the current guide, and see how it compares to your plotted course and interval positions.

4) If you meet unfavorable currents, adjust your departure time until you’ve eliminated as many bad current choices as you can.

As you plan, remember that any currents you catch well (or badly) will affect your arrival time at the next interval, so your results will vary as you sail the course.

Tides, Currents, and Anchoring

Anchoring in areas with extreme tides is a challenge, but failing to account for the tide even in less extreme waters can still cause a problem. And strong currents will affect your comfort if you’re not careful. We addressed this topic in some detail last year, so we’ll just give a quick recap here.

Tide, Scope, and Extremes

- When you anchor mid-tide, always estimate how much tidal change you have at high tide and include it in your scope.

- Extreme tides can lead to dragging anchors if you don’t use enough scope.

- Make sure at extremely low tides you don’t have so much scope out that you hit your neighbors.

Currents

- Anchoring in a strong tidal current may cause your anchor to continually pull out and reset as the current changes. Consider using a dual anchor setup, unless other boats with single anchors are nearby.

- Strong currents may push your boat into odd or uncomfortable positions, wrap your rode under your boat, or turn your bow well out of the wind.

- Posted in Blog, Boat Care, Boating Tips, Cruising, Fishing, iNavX, iNavX: How To, Navigation, News, Reviews, Sailing, Sailing Tips

- 1 Comment

- Tags: Currents, Tides

May 13, 2025 at 6:24 pm, Duncan Thomson said:

All good, but when are we going to get tides and currents integrated into iNavX???